Student Sues Pepsi for $37M Pepsi Fighter Jet Lawsuit, The Wild Lawsuit That Changed Advertising Forever

Business student John Leonard sent PepsiCo a $700,008.50 check demanding a Harrier fighter jet after seeing it advertised in a 1996 commercial for 7 million Pepsi Points. Pepsi refused, leading to Leonard v. Pepsico, Inc.—a landmark contract law case that ruled advertisements are generally not binding offers. Judge Kimba Wood dismissed the lawsuit in 1999, finding no reasonable person would believe a $37.4 million jet was truly available for $700,000.

Case Status: Closed. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed Judge Wood’s decision in 2000. After the lawsuit, Pepsi modified the commercial to require 700 million points and added “just kidding” disclaimer.

What Is the Pepsi Fighter Jet Lawsuit About?

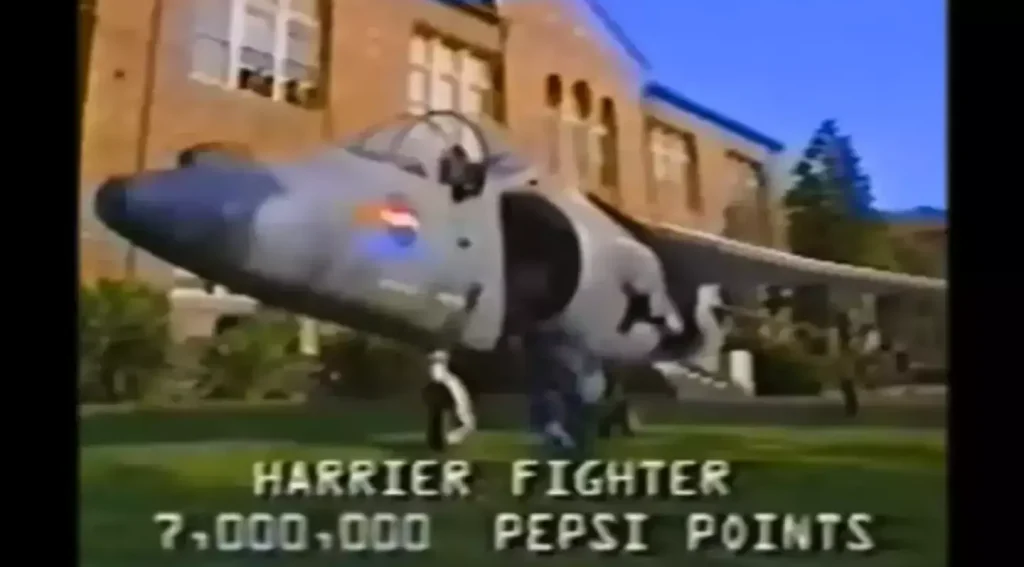

In March 1996, Pepsi launched “Pepsi Stuff,” its largest promotional campaign in company history, allowing customers to earn points redeemable for branded merchandise. A television commercial showed a teenager landing a Harrier fighter jet at his high school with text reading “HARRIER FIGHTER JET 7,000,000 PEPSI POINTS”.

Most viewers recognized the jet as part of Pepsi’s humor, but 21-year-old Seattle student John Leonard saw it as a legitimate business opportunity. The promotion allowed Pepsi Points to be purchased directly for 10¢ each—Leonard calculated acquiring the jet would cost $700,000, far less than the jet’s $37.4 million retail value.

Leonard recruited investor friend Todd Hoffman, who supplied the necessary funds. Following promotion rules, Leonard sent 15 Pepsi Point labels, a check for $700,008.50 (including $10 shipping), and an order form requesting delivery of one Harrier jet.

The Parties Involved

Plaintiff: John Leonard, 21-year-old business student from Seattle attending Shoreline Community College

Co-Investor: Todd Hoffman, who provided the $700,000 funding

Defendant: PepsiCo, Inc., the Purchase, New York-headquartered beverage company

Legal Representatives: Lawrence “Larry” Schantz represented Leonard initially, with Michael Avenatti later joining the legal team

Presiding Judge: Judge Kimba Wood, United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

Key Legal Claims Explained

Leonard filed suit in Miami accusing PepsiCo of breach of contract, fraud, deceptive and unfair trade practices, and misleading advertising. Leonard’s legal argument centered on unilateral contract theory—that Pepsi’s commercial constituted a legal offer with specific terms (7 million points for a Harrier jet) that could be accepted by delivering the required points.

The central question was whether PepsiCo’s commercial constituted a binding offer under contract law principles. Leonard contended the ad presented clear terms and that he had unequivocally accepted by tendering payment.

PepsiCo’s defense argued the commercial was “puffery”—exaggerated statements a reasonable person would not take literally. Pepsi asserted that depicting a teenager flying a military jet to school was obviously absurd and not a genuine offer.

Timeline of Events Leading to the Lawsuit

March 1996: Pepsi launches “Pepsi Stuff” campaign with television commercials featuring the Harrier jet prize

February 1996: Leonard first sees the commercial during a Pacific Northwest test run

1996: Leonard sends PepsiCo 15 Pepsi Point labels and check for $700,008.50 requesting one Harrier jet

1996: Pepsi rejects Leonard’s order, returns his check, offers two Pepsi coupons, and states the commercial was meant as a joke

1996: Leonard and Hoffman recruit attorney Lawrence Schantz, who sends demand letter to Pepsi

1996: Pepsi counter-sues Leonard and Hoffman, seeking declaratory judgment that it had no obligation to provide a Harrier jet

1996-1999: Case originally filed in Florida, later transferred to federal court in Manhattan

August 5, 1999: Judge Kimba Wood rules in Pepsi’s favor, granting summary judgment

2000: United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirms Judge Wood’s decision

Court Rulings and Legal Reasoning

Judge Wood rejected Leonard’s claims and denied recovery on multiple grounds under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56. The court’s reasoning included three primary legal bases:

Advertisements Are Not Offers: Under contract law, advertisements are typically invitations to negotiate rather than binding offers. The court held the commercial featuring the jet did not constitute an offer under the Restatement (Second) of Contracts.

Objective Reasonableness Standard: For a contract to form, an offer must be one a reasonable person would interpret as serious. The court concluded no objective person could believe Pepsi was seriously offering a multi-million-dollar military-grade jet for $700,000 worth of Pepsi Points.

Judge Wood specifically noted: “No school would provide landing space for a student’s fighter jet, or condone the disruption the jet’s use would cause”. The court found the Harrier Jet’s military functions—attacking and destroying targets, armed reconnaissance, and anti-aircraft warfare—made depicting it as transportation to school “clearly not serious”.

Statute of Frauds: Even if the commercial had constituted an offer, the alleged contract would be unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds, which requires contracts for goods over $500 to be in writing and signed by the party to be charged. Pepsi never signed anything indicating intent to transfer a Harrier jet.

Lack of Definite Terms: The court found the advertisement was not sufficiently definite because it reserved offer details to the Pepsi Stuff catalog, where the jet was never actually listed.

Leonard also argued a federal judge couldn’t decide the matter—that a jury of “Pepsi Generation” members should rule. The court rejected this claim.

Legal Precedents and Similar Cases

Leonard v. Pepsico has become one of the most-taught cases in law schools today. According to Dean Sudha Setty of CUNY School of Law, “It’s a case that easily captures the public imagination because it’s relatable,” unlike obscure business contract disputes.

The case reaffirmed the clear-cut rule that advertisements are not ordinarily considered offers and emphasized that advertisements cannot be considered offers if taken in jest by a reasonable person.

The case established important precedents for:

- Distinguishing advertisements from binding offers

- Applying objective reasonableness standards to promotional materials

- Defining “puffery” in advertising law

- Protecting companies from liability for humorous or exaggerated marketing

Recent Developments and Cultural Impact

In 2022, the saga made headlines again with Netflix’s docuseries “Pepsi, Where’s My Jet?” which explored the legal battle, marketing fiasco, and larger implications of misleading advertisements.

The case highlights how Pepsi’s marketing approach backfired when humor wasn’t properly framed, leading to confusion and lawsuits. The duo made history as they changed advertising practices, with disclaimers now an integral part of many commercials.

Pepsi never cashed Leonard’s check, so there was no case for fraud. After Leonard’s lawsuit was filed, Pepsi continued airing the commercial with modifications—increasing points from 7 million to 700 million and adding “just kidding” text.

Expert Analysis and Implications

Pepsi’s marketing blunder highlights the need for brands to be clear in their messaging—humor and exaggeration can work wonders, but campaigns not properly framed can lead to confusion, outrage, or lawsuits. Including relevant disclaimers helps brands protect themselves from potential legal disputes.

Companies must step into their customers’ shoes and anticipate potential misinterpretations before launching campaigns. Just because a brand finds something funny doesn’t mean its audience will interpret it the same way.

The case offers critical lessons for businesses in the age of viral marketing:

- Always include clear disclaimers on promotional materials

- Consider how reasonable consumers might interpret advertising

- Understand the legal distinction between “puffery” and binding offers

- Document that promotional items match catalog listings

Pepsi estimated the Pepsi Stuff campaign cost $200 million to roll out (equivalent to $350 million today), including $125 million worth of merchandise. Despite the lawsuit, one 1996 Pepsi executive called it “by far the most successful promotion” the company had ever run.

FAQ: Common Questions About the Pepsi Fighter Jet Lawsuit

What was the final outcome of the Pepsi fighter jet lawsuit?

Judge Kimba Wood ruled in Pepsi’s favor in August 1999, stating “No objective person could reasonably have concluded that the commercial actually offered consumers a Harrier jet”. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed this decision in 2000.

Did John Leonard receive any compensation?

No. Pepsi returned Leonard’s check and offered two Pepsi coupons. Leonard received no monetary settlement or the fighter jet.

How much did Leonard actually spend on the lawsuit?

Leonard secured $700,000 from investor Todd Hoffman to purchase the Pepsi Points. Legal costs were not publicly disclosed, though the case went through district and appeals courts.

Is the Pepsi fighter jet commercial still aired today?

After the lawsuit, Pepsi continued airing the ad but modified it to require 700 million points (up from 7 million) and added “just kidding” disclaimer text.

What type of fighter jet was featured in the commercial?

The commercial showcased a computer-generated Pepsi-branded AV-8 Harrier II, a vertical takeoff jet manufactured by McDonnell Douglas valued at approximately $37.4 million at the time.

Could Leonard have legally owned a Harrier jet if he won?

Pepsi argued that purchasing a Harrier jet was illegal, contrary to earlier statements. A Defense Department spokesman clarified a fully demilitarized jet probably wouldn’t have been much fun anyway.

Where can I learn more about this case?

The case is available as Leonard v. Pepsico, Inc., 88 F. Supp. 2d 116 (S.D.N.Y. 1999), aff’d 210 F.3d 88 (2d Cir. 2000). Netflix’s 2022 docuseries “Pepsi, Where’s My Jet?” provides comprehensive coverage of the legal battle.

Legal Disclaimer: This article provides factual information about the Pepsi fighter jet lawsuit based on verified court documents, news sources, and legal filings. It is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Case details and status are subject to change as litigation progresses. For specific legal advice regarding similar matters, please consult with a qualified attorney. Always verify current case information through official court records and reputable legal news sources.

Related Articles:

- Facebook Lawsuit Payout Latest Today Update: Active Settlements, Eligibility & Payout Amounts

- Progressive Class Action Lawsuit: Multiple Settlements Totaling Over $200 Million Impact Thousands of Policyholders

- Wells Fargo Class Action Lawsuits 2025: $2 Billion in Settlements—Are You Owed Money?

Sources:

- Leonard v. Pepsico, Inc. – Wikipedia

- Leonard v. Pepsico Court Case Explainer – Netflix

- The Time Pepsi Got Sued for a $33M Fighter Jet – The Hustle

About the Author

Sarah Klein, JD, is a licensed attorney and legal content strategist with over 12 years of experience across civil, criminal, family, and regulatory law. At All About Lawyer, she covers a wide range of legal topics — from high-profile lawsuits and courtroom stories to state traffic laws and everyday legal questions — all with a focus on accuracy, clarity, and public understanding.

Her writing blends real legal insight with plain-English explanations, helping readers stay informed and legally aware.

Read more about Sarah