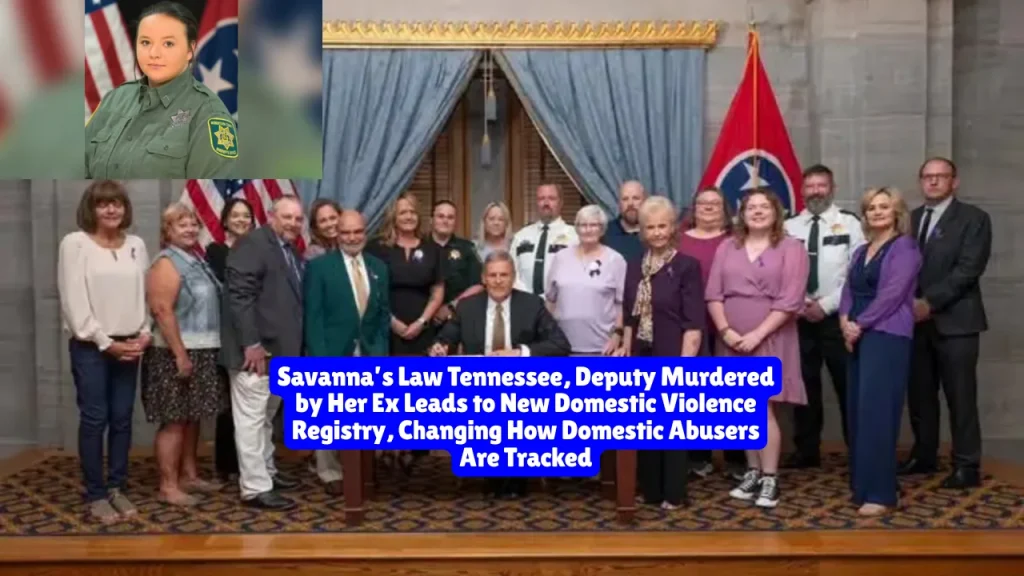

Savanna’s Law Tennessee, Deputy Murdered by Her Ex Leads to New Domestic Violence Registry, Changing How Domestic Abusers Are Tracked

Savanna’s Law in Tennessee creates the nation’s first public registry for repeat domestic violence offenders. The law, which took effect January 1, 2026, requires the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation to maintain an online database listing anyone convicted of at least two domestic violence offenses against domestic abuse victims. The registry includes names, photos, conviction dates, and counties of conviction.

A 22-year-old sheriff’s deputy called 911 on January 19, 2022, saying her ex-boyfriend showed up at her house uninvited—again. Four days later, Deputy Savanna Puckett was found shot to death inside her burning Springfield home. Her ex, James Jackson Conn, had a documented history of domestic violence arrests. But that information wasn’t easy to access. Now, Tennessee is making sure no one else has to search through scattered court records to find out if someone has a pattern of abuse.

Who Was Savanna Puckett and What Happened?

Savanna Puckett started working at the Robertson County Sheriff’s Office in 2017 as a corrections officer. She got promoted to booking officer, then became a patrol deputy in May 2020. She was 22 years old when her ex-boyfriend murdered her.

On January 23, 2022, Puckett didn’t show up for her 5 a.m. shift. Deputies went to check on her. They found her home on fire and her body inside with gunshot wounds.

James Jackson Conn, her ex-boyfriend, was arrested that same day and charged with first-degree murder. He’d been arrested for domestic assault against Puckett before. The restraining order she had against him had expired just weeks earlier.

Conn pleaded guilty in August 2023 and got life in prison without parole.

What Actually Is Savanna’s Law in Tennessee?

Savanna’s Law, officially House Bill 1200 and Senate Bill 324, created Tennessee’s Domestic Violence Offender Registry. Governor Bill Lee signed it into law on May 6, 2024. It went live on January 1, 2026.

The law requires the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation to maintain a public online registry listing anyone convicted of two or more domestic violence offenses against domestic abuse victims.

Here’s what shows up on the registry:

- Offender’s full name

- Photo

- Date of each conviction

- County where each conviction happened

The registry doesn’t include addresses, which makes it different from sex offender registries.

Who Has to Register Under Savanna’s Law?

You end up on the registry if you get convicted of at least two qualifying domestic violence offenses. These include:

Domestic assault – Intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly causing bodily injury to a domestic abuse victim

Aggravated domestic assault – Domestic assault that causes serious bodily injury, involves a deadly weapon, or strangulation

Stalking – When the victim is a domestic abuse victim

Aggravated stalking – When the victim is a domestic abuse victim

Violation of an order of protection – Second or subsequent violations

The convictions have to be against domestic abuse victims, which Tennessee law defines as current or former spouses, people who live together or used to live together, people who are dating or used to date, people who have a child together, and family members.

How Does the Registry Actually Work?

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation runs the registry. When someone gets convicted of a second qualifying offense, the court clerk has to notify TBI within 10 business days.

TBI then adds that person’s information to the public database.

Anyone can search the registry for free at the TBI website. You can search by name, county, or just browse the entire list.

The information stays on the registry as long as the person is alive. It doesn’t come off after a certain number of years like some registries.

What Tennessee Lawmakers Say About Savanna’s Law

Representative Bryan Terry, a primary sponsor of the bill, said the registry gives people “a tool to protect themselves and their families.” He pointed out that domestic violence victims often don’t know their abuser has a history with other people.

Senator Janice Bowling, another sponsor, said: “This registry will save lives. It’s that simple.”

At the bill signing, Savanna’s mother Diane told reporters: “I don’t want anyone else to go through what we went through. If this registry can help even one person see the warning signs, it’s worth it.”

Is Tennessee the First State to Do This?

Yes. Tennessee is the first state in the country to create a public domestic violence offender registry. Other states have talked about it, but Tennessee actually got it done.

Some states maintain domestic violence databases, but they’re only accessible to law enforcement or require victims to request specific information. Tennessee’s registry is completely public and searchable by anyone.

Who Opposed Savanna’s Law?

The ACLU of Tennessee opposed the bill. They argued it could make it harder for offenders to get housing and jobs, which might actually increase the risk of re-offense. They also worried about people being on the registry for relatively minor offenses.

Some defense attorneys raised concerns about due process and whether convictions from plea deals should count the same as trial convictions.

But the law passed with strong bipartisan support—79-13 in the House and 27-2 in the Senate.

What’s Not on the Registry?

The registry doesn’t include:

- Home addresses

- Work addresses

- Phone numbers

- Email addresses

- Social media accounts

- Vehicle information

- Details about the crimes beyond conviction dates and counties

This was intentional. Lawmakers wanted to balance public safety with concerns about vigilantism and making it impossible for offenders to reintegrate into society.

Can You Get Off the Registry?

No. Once you’re on Tennessee’s domestic violence offender registry, you stay on it for life. There’s no process to petition for removal, even if you’ve completed all your sentences and stayed crime-free for decades.

This is different from some other registries that allow removal after a certain period.

How Does This Help Potential Victims?

The registry gives people a way to check if someone they’re dating or living with has a history of domestic violence. Before Savanna’s Law, you’d have to search court records in every county where someone might have lived—if you even knew where to look.

Now, a simple name search on the TBI website shows any qualifying convictions statewide.

Domestic violence advocates say this is huge because abusers often have patterns. Someone who hurt one partner is statistically more likely to hurt another.

What About Privacy Concerns?

Critics argue the registry violates privacy rights and could lead to harassment of people who’ve already served their time. They point out that Tennessee doesn’t have public registries for people convicted of other serious crimes like robbery or assault against non-domestic victims.

Supporters counter that domestic violence is different because it happens in intimate relationships where victims often don’t have access to their abuser’s criminal history until it’s too late.

Recent Updates and Current Status

The registry launched on January 1, 2026. As of early January, TBI was still adding historical convictions to the database. Anyone convicted of qualifying offenses before 2026 is supposed to be added retroactively.

Some counties have been faster than others at reporting old convictions to TBI. The agency says it expects the registry to be fully populated with historical data by mid-2026.

Several other states have introduced similar legislation since Tennessee passed Savanna’s Law. Kentucky, Alabama, and Georgia all have bills pending that would create domestic violence registries modeled on Tennessee’s law.

What Happens If Someone Doesn’t Register?

Here’s the thing—offenders don’t actually have to do anything to “register.” This isn’t like sex offender registration where the person has to show up in person and provide information.

Instead, court clerks automatically notify TBI when someone gets convicted of a qualifying offense. TBI adds the information to the registry. The offender doesn’t have to take any action.

So there’s no crime for failing to register because there’s nothing the offender is required to do.

How Do Other States Handle This?

Most states don’t have public domestic violence registries at all. Some have internal law enforcement databases that aren’t accessible to the public.

California has a domestic violence restraining order database, but it’s only for active restraining orders, not criminal convictions.

Several states, including Florida and Texas, have proposed domestic violence registries but haven’t passed them into law yet.

What Do Domestic Violence Experts Say?

Opinions are split. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence supports public awareness tools but hasn’t taken an official position on registries specifically.

Some local Tennessee domestic violence shelters support the law. The director of one Nashville shelter told reporters: “Anything that helps survivors make informed decisions about their safety is a good thing.”

Others worry the registry might create a false sense of security. Just because someone isn’t on the registry doesn’t mean they’re not dangerous—they might not have been convicted yet, or they might have only one conviction instead of two.

Frequently Asked Questions About Savanna’s Law Tennessee

What is Savanna’s Law in Tennessee?

Savanna’s Law creates a public domestic violence offender registry maintained by the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation. Anyone convicted of two or more qualifying domestic violence offenses gets listed on the registry with their name, photo, conviction dates, and counties of conviction.

When did Savanna’s Law take effect?

January 1, 2026. Governor Bill Lee signed the law on May 6, 2024, and it went into effect at the start of 2026.

Who is the law named after?

Deputy Savanna Puckett, a 22-year-old Robertson County sheriff’s deputy who was murdered by her ex-boyfriend on January 23, 2022. Her ex had a history of domestic violence arrests.

How do I search the Tennessee domestic violence registry?

Go to the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation website at tn.gov/tbi. The registry is publicly searchable by name or county.

What convictions put you on the registry?

Two or more convictions for domestic assault, aggravated domestic assault, stalking of a domestic victim, aggravated stalking of a domestic victim, or repeat violations of orders of protection.

Does everyone with a domestic violence conviction go on the registry?

No. You need at least two qualifying convictions against domestic abuse victims. One conviction isn’t enough.

Can you get removed from the registry?

No. The registry is permanent. There’s no process to petition for removal.

Is Tennessee the only state with this registry?

Yes. Tennessee is the first state in the country to create a public domestic violence offender registry.

What information shows up on the registry?

Name, photo, date of each conviction, and county of each conviction. The registry does not include addresses.

Do offenders have to register themselves?

No. Court clerks automatically notify TBI when someone gets convicted. The offender doesn’t have to take any action.

Resources for Tennessee Domestic Violence Support

Tennessee Coalition to End Domestic and Sexual Violence

- Website: tncoalition.org

- 24/7 Hotline: 1-800-356-6767

National Domestic Violence Hotline

- 24/7 Support: 1-800-799-7233

- Text: START to 88788

Tennessee Bureau of Investigation Registry

- Search the domestic violence offender registry at tn.gov/tbi

Legal Aid of Tennessee

- Free legal help for domestic violence survivors

- Website: las.org

About the Author

Sarah Klein, JD, is a licensed attorney and legal content strategist with over 12 years of experience across civil, criminal, family, and regulatory law. At All About Lawyer, she covers a wide range of legal topics — from high-profile lawsuits and courtroom stories to state traffic laws and everyday legal questions — all with a focus on accuracy, clarity, and public understanding.

Her writing blends real legal insight with plain-English explanations, helping readers stay informed and legally aware.

Read more about Sarah