Dicamba Lawsuit Settlement, Farmers Win $400M—But 15 Million Acres Lost and No Dicamba for 2025

$400 million. That’s what Bayer agreed to pay American farmers whose crops were destroyed by dicamba—a herbicide so volatile it can drift for miles, turning healthy soybeans into twisted, stunted plants that produce 30% less yield.

But here’s what that number doesn’t tell you: An estimated 15 million acres of soybeans have been damaged since 2016. Vineyards across 12,000 square miles of California were destroyed. Peach orchards in Missouri lost entire harvests. And thousands of farmers watched their neighbors’ chemical choices wipe out their livelihoods—while crop insurance refused to pay a dime.

The dicamba settlement was supposed to bring closure. Instead, it’s revealed something more troubling: Even a $265 million jury verdict and a $400 million settlement couldn’t stop the damage. Federal courts have now vacated dicamba registrations twice—and as of 2025, over-the-top dicamba use is banned nationwide.

If you’re a farmer whose crops were damaged by dicamba drift, here’s what you need to know about the settlement, who qualifies for compensation, where the lawsuits stand now, and why dicamba might never return to American fields.

What Is Dicamba and Why Did It Cause So Much Damage?

Dicamba is a selective herbicide that’s been used since the 1960s to kill broadleaf weeds like pigweed, chickweed, and dandelions. For decades, it was only applied before crops emerged from the ground—what’s called “pre-emergent” use.

That changed in 2016 when Monsanto (now owned by Bayer) introduced genetically modified “dicamba-resistant” soybean and cotton seeds. These seeds were engineered to survive direct application of dicamba while the crops were growing—called “over-the-top” use.

The promise: Farmers could spray dicamba directly on their crops during the growing season to kill “superweeds” that had developed resistance to glyphosate (Roundup).

The problem: Dicamba is extremely volatile. It vaporizes after application and drifts—sometimes for miles—destroying any crops that aren’t genetically modified to resist it.

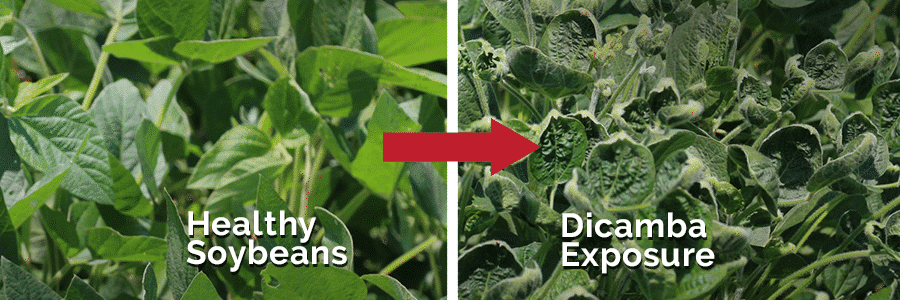

What Dicamba Damage Looks Like:

- Cupped, curled, or crinkled leaves

- Stunted plant growth

- Leaf elongation and twisting (“trumpeting”)

- Epinasty (abnormal bending and twisting)

- Discoloration and wrinkling

- Reduced yields of 10-30% or complete crop loss

Even the smallest exposure can devastate non-resistant crops. And because dicamba turns into vapor, it doesn’t just affect the field next door—it can damage crops miles away, often crossing state lines.

The Lawsuits: How Farmers Took On Monsanto and BASF

The dicamba crisis didn’t happen by accident. According to lawsuits filed by farmers across more than 20 states, Monsanto knew this would happen.

The Core Allegations:

- Monsanto released dicamba-resistant seeds in 2015—before the EPA approved a new, supposedly “safer” dicamba formula

- Farmers who bought the resistant seeds had no approved herbicide to spray on them

- Many farmers used older, more volatile dicamba formulations out of desperation

- Even after EPA approved new formulations (XtendiMax, Engenia, Tavium) in late 2016, they were still highly volatile

- Monsanto and BASF knew the new formulations would drift and damage non-resistant crops

- They marketed and sold the products anyway, essentially conducting a real-world experiment at farmers’ expense

By February 2018, the U.S. Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation consolidated 11 lawsuits into a single MDL (Multidistrict Litigation) in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri, presided over by Judge Stephen N. Limbaugh, Jr.

Eventually, approximately 170 plaintiffs joined the MDL, representing farmers from multiple states whose crops suffered dicamba damage between 2015 and 2020.

Related Lawsuit: Rusty Moore vs Megan Boser Traffic Stop Lawsuit, Minnesota Trooper Arrested Man With 0.00 BAC—He Missed His Daughter’s Graduation and Lost His CDL

The $265 Million Verdict That Changed Everything: Bader Farms v. Monsanto

The first case to go to trial was Bader Farms v. Monsanto and BASF.

Bill Bader owns the largest peach farm in Missouri. His family had been growing peaches in southeastern Missouri for generations. In 2015, dicamba drift from neighboring farms started killing his peach trees.

It happened year after year. Thousands of trees weakened, produced smaller fruit, or died entirely. Bader testified that he lost entire harvests while watching neighboring cotton farms spray dicamba directly onto their crops.

After a three-week trial in Cape Girardeau in January 2020, the jury delivered a stunning verdict:

- $15 million in compensatory damages – to cover the actual losses to Bader’s peach orchard

- $250 million in punitive damages – punishment for Monsanto and BASF’s conduct

The jury found both companies equally liable.

Why the Punitive Damages Were So High:

Punitive damages are awarded when a defendant’s conduct is particularly harmful or reckless. In this case, the jury agreed with Bader’s claim that Monsanto and BASF knew dicamba would drift and damage neighboring crops—even after reformulation—and sold the products anyway.

Judge Limbaugh later reduced the punitive damages to $60 million (still a massive penalty). Both sides appealed. In July 2022, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed in part, reversed in part, and sent the case back for a new trial on punitive damages only.

The case was eventually settled, though terms weren’t publicly disclosed.

But the damage was done—to Monsanto’s reputation and to any hope of defending the remaining 140+ lawsuits waiting in line.

The $400 Million Settlement: Who Got Paid and How Much

Facing mounting lawsuits and the Bader Farms verdict, Bayer (which acquired Monsanto in 2018) agreed to settle the MDL.

Settlement Breakdown:

- $300 million – for soybean producers whose crops were damaged by dicamba drift between 2015-2020

- Up to $100 million additional – for producers of non-soybean crops (cotton, orchards, specialty crops, gardens)

- Estimated $400 million total – including attorneys’ fees, litigation expenses, and claims administration costs

The settlement was announced in June 2020. Claims filing opened on December 29, 2020, with a deadline of May 28, 2021.

Who Qualified for Compensation:

- Commercial soybean producers whose crops were damaged by dicamba application from neighboring farms or fields

- Damage must have occurred between 2015 and 2020

- Claimants had to provide evidence of crop damage consistent with dicamba exposure

- Producers of non-soybean crops (orchards, vineyards, specialty crops) were covered under a separate settlement track

How Much Did Farmers Receive:

Settlement amounts varied based on:

- Number of acres affected

- Severity of damage

- Documented yield loss

- Whether damage was partial or total crop loss

- How many total claims were filed (more claims = smaller per-farmer payouts)

The exact payout amounts haven’t been publicly disclosed, but based on the $300 million fund divided among thousands of claims, most farmers likely received between $10,000 and $100,000 depending on their losses.

All approved claims have now been paid. The final round of payments was completed in late 2021, and the settlement is now closed to new claims.

California Vineyard Lawsuit: $500 Million Case Still Ongoing

While soybean farmers settled, California vineyard owners filed a separate lawsuit that’s still active.

In 2022, owners of more than 50 vineyards sued Bayer, BASF, and other dicamba manufacturers after drift from nearby cotton fields damaged approximately 12,000 square miles of vineyards.

What Makes This Case Different:

- Vineyards are permanent crops—once grapevines are damaged, they take years to recover or must be replanted entirely

- The economic loss is far greater than annual crops like soybeans

- Plaintiffs are seeking more than $500 million in damages

- The case focuses on Monsanto’s knowledge that dicamba would drift into high-value specialty crop areas

This case remains in litigation as of November 2025, with no settlement announced.

The EPA Ban: Why Dicamba Is Unavailable for 2025

Here’s the twist: Even while farmers were winning hundreds of millions in court, dicamba kept getting approved for use—until federal judges said enough.

The Legal Timeline:

2016: EPA approves first-ever “over-the-top” dicamba use for genetically modified crops.

June 2020: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals vacates EPA’s dicamba registration, finding the agency violated the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). The court noted that in approving dicamba, EPA “failed to examine how dicamba use would tear the social fabric of farming communities.”

October 2020: Just four months later, EPA re-approves dicamba for over-the-top use through 2025, claiming new application restrictions would prevent damage.

2021: EPA admits in its own report that application restrictions failed and dicamba continued causing massive drift damage.

February 6, 2024: The U.S. District Court of Arizona vacates EPA’s 2020 registration again, finding EPA violated FIFRA by failing to properly assess risks to non-users and environmental impacts.

Current Status: No dicamba herbicide is approved for over-the-top use in 2025. The products XtendiMax (Bayer), Engenia (BASF), and Tavium (Syngenta) cannot be sold or used for in-crop applications.

What About 2026 and Beyond?

On July 23, 2025, the EPA announced it’s proposing to unconditionally register all three dicamba products—meaning they’d remain approved for at least 15 years rather than expiring in 2-5 years like previous conditional registrations.

The public comment period closed on August 22, 2025. If EPA approves the new labels, dicamba could return for the 2026 growing season.

But legal challenges are almost certain. Environmental groups and farmers who don’t use dicamba have repeatedly sued over every EPA approval—and won twice. A third lawsuit is likely.

The Real Cost: 15 Million Acres and Broken Communities

The numbers tell only part of the story.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, up to 15 million acres of soybeans have been damaged by dicamba drift since 2016.

That’s roughly the size of West Virginia—entirely destroyed or damaged by a herbicide that wasn’t supposed to drift.

Beyond Soybeans:

- Orchards: Peach, apple, and other fruit trees killed or weakened across Missouri, Arkansas, and neighboring states

- Vineyards: 12,000 square miles of California grapevines damaged

- Gardens and Forests: Home gardens, ornamental plants, and native vegetation destroyed

- Beekeepers: Sharp drops in honey production due to dicamba suppressing flowering plants bees need for sustenance

The Social Damage:

The Ninth Circuit noted something that statistics can’t capture: dicamba “tore the social fabric of farming communities.”

Neighbors who had farmed side-by-side for generations became enemies. Farmers who chose to plant dicamba-resistant crops and spray dicamba destroyed their neighbors’ harvests. Lawsuits pitted farmer against farmer.

Some farmers felt pressured to switch to dicamba-resistant seeds just to protect themselves—even if they didn’t want to. Others abandoned crops they’d grown for decades because dicamba drift made them unviable.

Rural America fractured over a chemical company’s profit strategy.

What Farmers Should Know Now: Your Rights and Options

If you’re a farmer dealing with dicamba issues, here’s what you need to know:

If You Suffered Crop Damage Between 2015-2020:

The Bayer MDL settlement deadline has passed (May 28, 2021). All approved claims have been paid. You cannot file new claims under that settlement.

However, if you opted out of the class action, you may still have individual claims. Contact an agricultural litigation attorney immediately to discuss whether you can file an independent lawsuit. Statutes of limitations vary by state.

If You Suffered Damage After 2020:

You may have grounds for a separate lawsuit. The MDL settlement only covered damage through 2020. EPA admitted in 2021 that dicamba continued causing damage despite supposedly improved formulations.

Consult with an attorney experienced in agricultural product liability cases.

If You’re Planning for 2025:

Dicamba is NOT available for over-the-top use in 2025. Do not attempt to use old stocks or formulations not labeled for in-crop application—this violates federal law and could result in criminal penalties.

Alternative weed control strategies are necessary for the 2025 growing season.

If You’re Planning for 2026:

Monitor EPA’s decision on the proposed unconditional registration. If approved, dicamba could return—but with stricter application restrictions aimed at reducing volatility and protecting endangered species.

Any new registration will likely face immediate legal challenges. Plan for uncertainty.

Comparing Dicamba to Other Herbicide Litigation: The Roundup Parallel

The dicamba lawsuits follow a familiar pattern for Bayer—though with a crucial difference.

Roundup (Glyphosate) Litigation:

Bayer faces over 100,000 lawsuits claiming Roundup causes non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and other cancers. Bayer has paid over $10 billion in settlements but continues fighting thousands of pending cases.

Key Difference:

Roundup lawsuits focus on health harm to humans. Dicamba lawsuits focus on economic harm to farmers and environmental damage.

Courts have been far more willing to hold Bayer accountable for dicamba’s drift damage than for Roundup’s alleged health effects. The evidence is clearer: You can see dicamba-damaged crops. You can prove yield loss. You can calculate economic harm.

What This Means:

Future agricultural product liability cases may focus more on economic and environmental harm rather than long-term health effects—a legal strategy that’s proven more successful for plaintiffs.

Related Legal Issues for Farmers

Dicamba litigation connects to broader legal issues affecting agricultural operations:

- Product liability lawsuits against manufacturers

- Class action settlements and claim procedures

- Environmental damage claims and property rights

- Wrongful death and economic loss claims

Key Legal Resources:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA)

- National Agricultural Law Center

- Penn State Center for Agricultural and Shale Law – Dicamba Tracker

Frequently Asked Questions About the Dicamba Lawsuit and Settlement

What was the dicamba lawsuit about?

The dicamba lawsuit involved thousands of farmers suing Monsanto (now Bayer), BASF, and other manufacturers for releasing dicamba-resistant seeds before a safe herbicide formulation was available, then selling volatile dicamba products that drifted onto neighboring farms and destroyed crops.

How much was the dicamba settlement?

Bayer agreed to pay up to $400 million total: $300 million for soybean producers and an additional $100 million for non-soybean crops, plus attorneys’ fees and administration costs. This came after a jury awarded $265 million to Bader Farms in the first trial.

Can I still file a dicamba claim?

No. The deadline for claims under the main MDL settlement was May 28, 2021. All approved claims have been paid and the settlement is closed. However, if you opted out of the class action or suffered damage after 2020, you may have individual claims—consult an agricultural litigation attorney.

Who qualified for the dicamba settlement?

Commercial farmers whose soybean crops or other commercial crops were damaged by dicamba application from neighboring properties between 2015 and 2020. Claimants needed evidence of crop damage consistent with dicamba exposure (cupped leaves, stunted growth, yield loss).

How much money did farmers receive from the settlement?

Settlement amounts varied based on acres affected, severity of damage, and total number of claims filed. While exact amounts weren’t publicly disclosed, most farmers likely received between $10,000 and $100,000 depending on their documented losses.

Why is dicamba banned in 2025?

On February 6, 2024, a federal court in Arizona vacated EPA’s registration of three dicamba products (XtendiMax, Engenia, Tavium) for over-the-top use, finding EPA violated federal law. No dicamba herbicide is currently approved for in-crop applications in 2025.

Will dicamba be available in 2026?

Possibly. In July 2025, EPA proposed unconditionally registering XtendiMax, Engenia, and Tavium for over-the-top use starting in 2026. A public comment period closed August 22, 2025. If approved, dicamba could return—but legal challenges are expected, and the timeline remains uncertain.

What does dicamba damage look like?

Dicamba-damaged plants show cupped or curled leaves, stunted growth, leaf twisting (“trumpeting”), epinasty (abnormal bending), discoloration, wrinkling, and reduced yields of 10-30% or complete crop loss. Even small exposures can devastate non-resistant crops.

Does crop insurance cover dicamba drift damage?

No. Federal crop insurance policies do not cover damage caused by herbicide drift, including dicamba. This left thousands of farmers with no compensation except through lawsuits or the settlement.

What happened in the Bader Farms case?

In February 2020, a jury awarded Bader Farms $265 million ($15M compensatory, $250M punitive damages) after Monsanto and BASF’s dicamba destroyed the Missouri peach farm. The judge later reduced punitive damages to $60 million. The case was appealed and eventually settled.

Can I sue my neighbor for using dicamba?

Potentially, yes. If your neighbor’s dicamba application damaged your crops, you may have claims for negligence, nuisance, or trespass under state law. However, proving your neighbor was the source (rather than drift from miles away) can be difficult. Consult a local agricultural attorney.

Why did Monsanto release dicamba-resistant seeds early?

According to lawsuits, Monsanto released the seeds in 2015 before EPA approved a new dicamba formulation for over-the-top use, creating a market for its seeds while farmers had no approved herbicide to spray on them. This allegedly pressured farmers to use older, more volatile dicamba formulations.

What states were most affected by dicamba damage?

Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois, Tennessee, North Carolina, Mississippi, Kentucky, Kansas, and other Midwest and Southern states reported the most damage. Over 20 states had farmers file lawsuits. California vineyards were also heavily impacted.

Are there other herbicides facing similar lawsuits?

Yes. Paraquat faces thousands of lawsuits claiming it causes Parkinson’s disease. Roundup (glyphosate) litigation continues with over 100,000 claims. Atrazine has faced environmental contamination claims. Agricultural chemical litigation is expanding as farmers and consumers demand accountability.

Final Thoughts: Justice Delayed, Damage Done

The dicamba settlement delivered $400 million to farmers whose crops were destroyed. That’s real money that helped some farms survive years of losses.

But it’s not justice.

Justice would have been Monsanto waiting to release dicamba-resistant seeds until a truly safe herbicide was ready. Justice would have been EPA protecting farmers and the environment instead of approving registrations that courts repeatedly overturned. Justice would have been crop insurance covering farmers whose neighbors’ choices destroyed their livelihoods.

Instead, American farmers got a multi-billion-dollar experiment conducted on their land without their consent.

15 million acres damaged. Thousands of farms hurt. Rural communities fractured. An entire industry’s trust in regulators and agricultural corporations shattered.

And now, after two court victories banning dicamba, EPA is proposing to bring it back—with an “unconditional” 15-year registration that would make it nearly permanent.

The fight isn’t over. It’s just entering a new phase.

For farmers dealing with dicamba damage or preparing for 2025’s dicamba-free growing season, the message is clear: Document everything. Preserve your rights. And don’t trust promises from chemical companies or regulators whose track records speak for themselves.

The dicamba story isn’t about one herbicide. It’s about who pays when corporations prioritize profits over safety—and whether American farmers have any real protection when the next “agricultural innovation” hits the market.

This article provides legal information based on public court records, government reports, and settlement documents. It should not be construed as legal advice. For specific guidance regarding dicamba damage claims or agricultural litigation, consult a qualified attorney experienced in agricultural product liability cases.

About the Author

Sarah Klein, JD, is a licensed attorney and legal content strategist with over 12 years of experience across civil, criminal, family, and regulatory law. At All About Lawyer, she covers a wide range of legal topics — from high-profile lawsuits and courtroom stories to state traffic laws and everyday legal questions — all with a focus on accuracy, clarity, and public understanding.

Her writing blends real legal insight with plain-English explanations, helping readers stay informed and legally aware.

Read more about Sarah