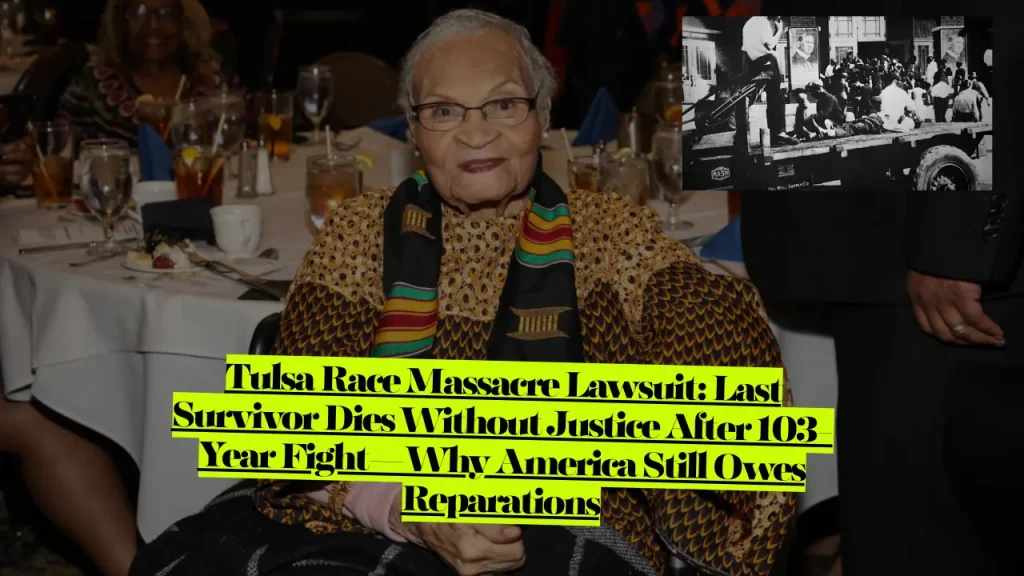

Tulsa Race Massacre Lawsuit, Last Survivor Viola Ford Fletcher Dies Without Justice After 103-Year Fight

BREAKING: Viola “Mother” Fletcher, the oldest survivor of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, died Monday at age 111—just five months after Oklahoma’s highest court dismissed her final chance at justice. She was 7 years old when white mobs burned her neighborhood to the ground. She spent 103 years waiting for America to say: “We owe you.”

America never did.

Her death leaves Lessie Benningfield Randle, 110, as the last known survivor of America’s worst single act of racial violence—a two-day terror campaign that killed an estimated 300 Black residents, destroyed 35 city blocks of “Black Wall Street,” and erased over $200 million in today’s dollars from the wealthiest Black community in the United States.

Fletcher’s attorney, Damario Solomon-Simmons, spent this past Friday night at her hospital bedside. “Mother Fletcher didn’t talk like someone who was ready to go,” he said. “She wasn’t done. She was tired—because this fight is exhausting—but her spirit was still in it.”

The Tulsa Race Massacre lawsuit represents one of the most significant reparations battles in American legal history. And its dismissal by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in June 2024 sent a devastating message: Even if you survived the massacre yourself, even if you’re still alive to testify, even if the courts admit your “grievance is legitimate and worthy of merit”—you’re still not owed anything.

Here’s what happened, why the lawsuit failed, and what it means for racial justice in America.

Related Lawsuit: Dicamba Lawsuit Settlement, Farmers Win $400M—But 15 Million Acres Lost and No Dicamba for 2025

What Was the Tulsa Race Massacre? The 1921 Destruction of Black Wall Street

If you’ve never heard of the Tulsa Race Massacre, you’re not alone. For decades, this history was deliberately buried, erased from textbooks, and hidden from the American narrative.

On May 31, 1921, Tulsa’s Greenwood District—known as “Black Wall Street”—was one of the most prosperous African American communities in the United States. It had its own hospitals, schools, churches, newspapers, theaters, restaurants, hotels, and over 200 thriving Black-owned businesses.

Within 24 hours, it was gone.

What sparked the violence: On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner, entered an elevator with Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator. What happened next remains disputed—most accounts suggest he accidentally stepped on her foot. She screamed. By the next day, the Tulsa Tribune published a sensationalized story claiming assault.

What happened next: A white mob gathered at the courthouse demanding to lynch Rowland. Black World War I veterans—men who had fought for America abroad—arrived to protect him from vigilante “justice.” A scuffle broke out. A gun fired. And then all hell broke loose.

The 18 hours of terror that followed:

- Up to 10,000 white Tulsans attacked Greenwood

- They burned 1,256 homes and destroyed 400 more

- They looted and destroyed two Black hospitals, eight churches, seven grocery stores, four hotels, and countless businesses

- They shot Black residents in the streets

- They dropped incendiary devices from airplanes—the first aerial bombing of an American city

- They detained over 6,000 Black survivors in makeshift internment camps

- An estimated 300 people were killed (the true number may never be known)

Insurance companies denied nearly every claim filed by Black survivors. No one was ever criminally prosecuted. The massacre was systematically erased from history—removed from textbooks, rarely discussed publicly, and buried in collective amnesia for decades.

Until three survivors decided to sue.

The Tulsa Race Massacre Lawsuit: Who Filed and What They Wanted

In 2020, nearly 100 years after the massacre, three survivors filed a historic lawsuit seeking reparations.

The Plaintiffs:

- Viola “Mother” Fletcher – 7 years old during the massacre (died November 24, 2025, at age 111)

- Hughes Van Ellis Sr. (known as “Uncle Redd”) – Fletcher’s younger brother, 6 months old during the massacre (died October 2023 at age 102)

- Lessie Benningfield Randle – 7 years old during the massacre (now 110, the last known survivor)

The Defendants:

- City of Tulsa

- Tulsa County

- Tulsa Regional Chamber of Commerce

- Oklahoma Military Department

- Tulsa County Sheriff

What the survivors sought:

The lawsuit didn’t ask for cash payments to individuals. Instead, it demanded:

- A detailed accounting of all property and wealth destroyed

- Construction of a hospital in North Tulsa

- Creation of a victims compensation fund

- Economic revitalization of the Greenwood community

- Recognition that ongoing racial and economic disparities stem directly from the massacre

The legal theory was simple but powerful: The massacre created a “public nuisance” that continues to harm the community today. The defendants not only failed to prevent the violence but actively participated in it—and then profited from it for over a century while Greenwood remained blighted.

Fletcher testified before Congress in 2021, 100 years after the massacre. “I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street,” she said. “I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams.”

She never stopped seeking justice.

Why the Oklahoma Supreme Court Dismissed the Lawsuit: The Legal Roadblock

On June 12, 2024, the Oklahoma Supreme Court delivered its ruling in Randle v. City of Tulsa: Dismissed. The vote was 8-1.

The court’s reasoning? The massacre happened too long ago. The legal claims didn’t fit within Oklahoma’s “public nuisance” statute. The lingering effects are “generational-societal inequities that can only be resolved by policymakers—not the courts.”

The court actually wrote:

“Plaintiffs’ grievance with the social and economic inequities created by the Tulsa Race Massacre is legitimate and worthy of merit. However, the law does not permit us to extend the scope of our public nuisance doctrine beyond what the Legislature has authorized.”

Translation: We know you were wronged. We know it was horrific. We know the harm continues. But we can’t help you.

Why Public Nuisance Failed:

Public nuisance law typically addresses ongoing conditions like pollution, blocked roads, or dangerous properties that continuously harm the community. The plaintiffs argued that the massacre created conditions—segregation, disinvestment, economic barriers, health disparities—that persist to this day.

The court disagreed. It ruled that extending public nuisance law to cover “historical tragedies and injustices” would exceed what Oklahoma lawmakers intended.

Why Unjust Enrichment Failed:

The plaintiffs also claimed the City of Tulsa and Chamber of Commerce profit from marketing “Black Wall Street” as a tourist attraction without returning benefits to the community or descendants.

The court found this argument insufficient.

The Statute of Limitations Problem:

Here’s the legal catch-22: If survivors had sued in 1921, they would have faced Jim Crow courts that wouldn’t have given them a fair hearing. But waiting until they could pursue justice meant facing modern courts that said they waited too long.

Lead attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons called this ruling the survivors’ last chance. “There is no going to the United States Supreme Court. There is no going to the federal court system. This is it.”

He filed a petition for rehearing. The Oklahoma Supreme Court denied it in September 2024.

The Federal Investigation: DOJ Confirms Massacre But Can’t Prosecute

After the Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissal, attorneys called on the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act.

On September 30, 2024, the DOJ announced it would conduct a review.

What the DOJ Found:

In January 2025, the Department of Justice released a groundbreaking 123-page report—the first official federal accounting of the massacre. The findings were damning:

- As many as 10,000 white Tulsans participated in the attack

- The violence was “so systematic and coordinated that it transcended mere mob violence”

- Tulsa police deputized hundreds of white men who immediately joined the assault

- Law enforcement disarmed Black residents trying to defend their homes, then detained them in internment camps

- City officials actively obstructed relief efforts and prevented Greenwood from rebuilding

“The Tulsa Race Massacre stands out as a civil rights crime unique in its magnitude, barbarity, racist hostility and its utter annihilation of a thriving Black community,” wrote Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke.

Why No Criminal Charges:

The DOJ concluded that federal prosecution is legally impossible because:

- All perpetrators are dead

- Statutes of limitations expired decades ago

- Federal hate crime laws didn’t exist in 1921

- No viable legal avenue remains for criminal prosecution

The report serves as historical acknowledgment—not justice.

The Economic Devastation: What Was Really Lost in 1921

Understanding the true scope of the Tulsa Race Massacre requires looking at the numbers—not just lives lost, but generational wealth stolen.

Immediate Property Damage:

According to the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921:

- 1,256 homes destroyed

- 400+ additional homes looted

- 2 Black hospitals burned

- 8 churches destroyed

- 7 grocery stores razed

- 2 schools burned

- Over 200 businesses destroyed

- More than $1.8 million in damage claims filed (over $27 million today)

Insurance companies denied all but one claim—a white shop owner was compensated for guns taken from his store.

The Wealth That Never Was:

A 2021 Brookings Institution analysis calculated the long-term economic impact:

“If 1,200 median priced houses in Tulsa were destroyed today, the loss would be around $150 million. The additional loss of other assets, including cash, personal belongings, and commercial property, might bring the total to over $200 million.”

But the real loss isn’t just property—it’s the compounding effect of stolen opportunity over four generations.

What That Wealth Could Have Done:

Brookings researchers calculated that if the stolen wealth had remained in the community:

- Thousands of Black students could have afforded college tuition

- Hundreds of families could have owned homes

- Dozens of new businesses could have launched

- The wealth gap between Black and white Tulsans would be dramatically smaller today

Instead, Greenwood descendants inherited trauma, displacement, and poverty where their grandparents had owned thriving businesses.

Viola Fletcher’s Life: 111 Years of Waiting for Justice

Viola Ford Fletcher was born on May 10, 1914, in Oklahoma. Her family had a nice home in Greenwood. The community had everything—doctors, grocery stores, restaurants, banks. It was an oasis for Black people during segregation.

She was 7 years old on May 31, 1921.

“The night of the Massacre I was woken up by my family,” she told Congress in 2021. “My parents and five siblings were there. I was told we had to leave. And that was it.”

Her family became nomadic sharecroppers, living in a tent and working in the fields. She never finished school beyond fourth grade. At 16, she returned to Tulsa and got a job cleaning and creating window displays in a department store.

During World War II, she worked as a welder in a shipyard. She raised three children. She spent decades caring for families as a housekeeper. She lived through Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement, the election of the first Black president, and the resurgence of white nationalism.

She told CBS News she thought about the massacre every day. “It just stays with me, you know, just the fear. I have lived in Tulsa since but I don’t sleep all night living there.”

In 2023, she published a memoir: Don’t Let Them Bury My Story.

On November 24, 2025, surrounded by family at a Tulsa hospital, Viola Fletcher died at 111—without ever receiving compensation, an apology from the state, or the justice she sought for 103 years.

Where the Case Stands Now: The Fight Continues

With Fletcher’s death, only one known massacre survivor remains alive.

Lessie Benningfield Randle, 110, continues the fight.

After the Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissal, Fletcher and Randle released a joint statement: “For as long as we remain in this lifetime, we will continue to shine a light on one of the darkest days in American history.”

Randle’s family issued a statement urging the courts to “honor the survivors while they are still with us” and noting that “Justice for Mother Randle and Mother Fletcher is overdue!”

What Happens Next:

The legal options are exhausted. The Oklahoma Supreme Court was the final avenue for state-level reparations. Federal criminal prosecution is impossible. The DOJ review acknowledged the horror but delivered no accountability.

The question now: Can Tulsa—and America—find a path to repair outside the courtroom?

Tulsa’s “Road to Repair”: $105 Million Plan Without Direct Payments

In June 2024, just days before the Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissed the lawsuit, Tulsa Mayor Monroe Nichols (the city’s first Black mayor) announced a $105 million “Road to Repair” initiative.

The plan would create:

- Housing fund – Address housing insecurity in North Tulsa

- Cultural preservation fund – Protect and promote Greenwood’s history

- Legacy fund – Support education and local businesses

The Controversial Part:

The plan explicitly does not provide direct cash payments to survivors or descendants.

Critics argue this is inadequate. Survivors like Fletcher and Randle spent their final years seeking acknowledgment and compensation—not more community programs. Descendants question why the city can invest $105 million in “repair” while denying that survivors deserve individual reparations.

Supporters say it’s a pragmatic solution that addresses ongoing disparities without triggering the legal and political backlash direct payments would face.

Why This Case Matters: The Battle Over Historical Reparations

The Tulsa Race Massacre lawsuit isn’t just about one city or one atrocity. It’s a test case for whether America will ever compensate victims of historical racial violence.

Other Reparations Efforts:

- Evanston, Illinois created the first municipal reparations program in 2021, offering housing benefits to Black residents affected by discriminatory policies. White residents sued in 2024, claiming reverse discrimination.

- California established a Reparations Task Force to study and recommend reparations for descendants of enslaved people. The report calls for billions in payments. The legislature hasn’t acted.

- H.R. 40, a bill to study federal reparations, has been introduced repeatedly since 1989. It has never passed.

The Legal Precedent Problem:

If the Oklahoma Supreme Court had ruled in favor of Fletcher and Randle, it would have opened the door for similar claims nationwide:

- Descendants of Rosewood massacre victims (1923)

- Survivors of the East St. Louis massacre (1917)

- Families affected by redlining, housing discrimination, and urban renewal

- Descendants of lynching victims

Courts fear a flood of historical claims. But that fear doesn’t erase the harm—it just leaves victims without remedy.

What Legal Scholars Say:

Martha F. Davis, writing for State Court Report, argues:

“The fact that a government abdicated its responsibility nearly 100 years ago and continued to do so in subsequent years does not absolve it of that responsibility today.”

Others point out the legal contradiction: Courts say the harm was too long ago—but the harm continues every day in North Tulsa’s poverty, health disparities, and lack of economic opportunity.

The Ongoing Search for Mass Graves: Tulsa’s Unfinished Investigation

While the legal battle played out, Tulsa has been searching for the massacre’s victims—literally digging up the truth.

In 2020, Mayor G.T. Bynum launched an archaeological investigation into mass graves. Researchers have found three sets of remains with gunshot wounds at Oaklawn Cemetery.

In June 2023, investigators identified their first victim: C.L. Daniel, a World War I veteran buried in an unmarked grave.

The search continues. Researchers believe dozens—potentially hundreds—of victims were buried in unmarked graves, thrown into the Arkansas River, or disposed of in ways that left no record.

The National Archives holds Red Cross records from the massacre showing 8,624 registered survivors and noting that death figures “are omitted because NO ONE KNOWS.”

Every excavation is a small step toward truth. But truth without accountability rings hollow.

What Descendants and Activists Are Demanding Now

With the legal system failing survivors, advocates are pushing for legislative and policy solutions.

Key Demands:

- Federal reparations legislation specific to the Tulsa Race Massacre

- State-level compensation fund for survivors and descendants

- Property restitution or fair market compensation for stolen land

- Economic investment in North Tulsa beyond symbolic programs

- Education mandates requiring the massacre be taught in Oklahoma schools

- National recognition including a federal memorial and museum

Why Direct Payments Matter:

Community programs are important, but they don’t address individual harm. Fletcher and Randle didn’t just lose property—they lost childhoods, educations, economic security, and the generational wealth that would have transformed their families’ futures.

No amount of money can undo that. But refusing to try sends a clear message about whose lives America values.

Related Legal Issues and Resources

The Tulsa Race Massacre lawsuit intersects with broader questions of civil rights litigation, wrongful death claims, statute of limitations challenges, and public nuisance law.

Key Legal Resources:

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division

- Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot

- National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Library of Congress Tulsa Race Massacre Archives

- Greenwood Cultural Center

Frequently Asked Questions About the Tulsa Race Massacre Lawsuit

What was the Tulsa Race Massacre lawsuit about?

The lawsuit, filed in 2020 by survivors Viola Fletcher, Hughes Van Ellis, and Lessie Benningfield Randle, sought reparations for the 1921 massacre that destroyed Tulsa’s Greenwood District. They argued the massacre created an ongoing “public nuisance” and that defendants unjustly enriched themselves while Greenwood remained economically devastated.

Who were the plaintiffs in the Tulsa Race Massacre lawsuit?

The three known living survivors: Viola Fletcher (age 107 when filed), her brother Hughes Van Ellis (age 100 when filed), and Lessie Benningfield Randle (age 106 when filed). They were all children during the massacre. Van Ellis died in 2023, and Fletcher died in November 2025, leaving only Randle.

Why did the Oklahoma Supreme Court dismiss the lawsuit?

The court ruled 8-1 that the massacre’s effects, while “legitimate and worthy of merit,” didn’t fall within Oklahoma’s public nuisance statute. The court said the lingering harm constitutes “generational-societal inequities” that only policymakers—not courts—can address. They also dismissed unjust enrichment claims.

How much money were the survivors seeking?

The lawsuit didn’t specify a dollar amount for individual survivors. Instead, it sought economic investment in North Tulsa, construction of a hospital, creation of a compensation fund for all victims and descendants, and a detailed accounting of lost property and wealth.

Can the survivors appeal the Oklahoma Supreme Court decision?

No. The Oklahoma Supreme Court is the state’s highest court. Attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons said this was “the final opportunity” for justice. The case cannot be appealed to federal courts because it’s based on state law claims.

What did the Department of Justice investigation find?

In January 2025, the DOJ released a 123-page report confirming that up to 10,000 white Tulsans systematically destroyed Greenwood, with active participation from law enforcement. However, the DOJ concluded no criminal prosecution is possible because perpetrators are dead and statutes of limitations expired decades ago.

How many people died in the Tulsa Race Massacre?

Contemporary estimates ranged from 36 to over 300. Historians now believe 100-300 people were killed, though the true number may never be known. The Red Cross noted deaths “are omitted because NO ONE KNOWS.” Many victims were buried in unmarked mass graves still being searched today.

Did insurance companies pay for the destroyed property?

No. Insurance companies denied nearly every claim filed by Black survivors. Only one person received compensation: a white shop owner for guns taken from his store. Over $1.8 million in claims (over $27 million today) were rejected.

What is Tulsa’s “Road to Repair” plan?

In June 2024, Tulsa Mayor Monroe Nichols announced a $105 million private trust to address disparities in North Tulsa through housing, cultural preservation, and business support. The plan does NOT provide direct cash payments to survivors or descendants, which critics say is inadequate.

Are there other survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre still alive?

Yes, one: Lessie Benningfield Randle, age 110. She is the last known living survivor of the massacre. Viola Fletcher died November 24, 2025, at age 111. Hughes Van Ellis died in October 2023 at age 102.

Can descendants of massacre victims still sue for reparations?

Legally, it’s extremely difficult. The Oklahoma Supreme Court ruling closed the door on public nuisance claims. Descendants face even higher legal hurdles than direct survivors because they must prove direct harm and overcome statute of limitations defenses. Most legal experts say state or federal legislation is the only viable path forward.

What happened to Dick Rowland, the man accused of assaulting Sarah Page?

All charges against Rowland were dropped. Sarah Page never pressed charges and disappeared from public record shortly after the massacre. Historians believe the alleged “assault” was Rowland accidentally stepping on her foot in the elevator.

Why was the Tulsa Race Massacre covered up for so long?

Local newspapers destroyed records. The massacre was removed from Oklahoma history textbooks. Survivors feared retaliation for speaking out. White Tulsa wanted to forget its role in the atrocity. The coverup lasted until the 1990s when historians and survivors began demanding the truth be told.

What can people do to support reparations for Tulsa massacre survivors?

Contact your congressional representatives urging federal reparations legislation. Support organizations working for justice like Justice for Greenwood Foundation. Donate to educational initiatives teaching this history. Amplify survivor stories and descendant voices. Push Oklahoma legislators to create a state compensation fund.

Final Thoughts: A Century of Denied Justice

Viola Fletcher spent 103 years—nearly her entire life—waiting for America to acknowledge that what happened in Tulsa was wrong. That her community didn’t deserve to be burned to the ground. That she and other survivors were owed more than silence and erasure.

She died without getting it.

Her brother Hughes never got it. And now, at 110 years old, Lessie Benningfield Randle fights alone—the last living witness to one of America’s worst atrocities, still waiting for justice that may never come.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court acknowledged the survivors’ “grievance is legitimate and worthy of merit.” But that acknowledgment means nothing without action. Without compensation. Without repair.

The court’s message was clear: Being right doesn’t mean you’ll get justice. Surviving doesn’t mean you’ll be compensated. And living long enough to tell your story doesn’t guarantee anyone will listen—or care.

The Tulsa Race Massacre lawsuit matters because it forced America to confront a question we’ve been avoiding for over a century:

Do we owe anything to the victims of racial violence?

Every court that dismissed this case said no. But Viola Fletcher’s final words to Congress still echo:

“I am 107 years old and have never seen justice. I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned.”

“We may not get justice in my lifetime,” she said, “but I pray that it comes soon.”

It didn’t. She died waiting.

The question now is whether America will continue making survivors wait—or whether we’ll finally choose justice before the last witness is gone.

This article provides legal information based on public court records, government reports, and historical documentation. It should not be construed as legal advice. For specific legal guidance, consult a qualified attorney.

About the Author

Sarah Klein, JD, is a licensed attorney and legal content strategist with over 12 years of experience across civil, criminal, family, and regulatory law. At All About Lawyer, she covers a wide range of legal topics — from high-profile lawsuits and courtroom stories to state traffic laws and everyday legal questions — all with a focus on accuracy, clarity, and public understanding.

Her writing blends real legal insight with plain-English explanations, helping readers stay informed and legally aware.

Read more about Sarah